Book Project: The Politics of Vice

In my dissertation and first book project, I trace the origins of a key idea: that political institutions should be designed to manipulate otherwise negative human traits, or ‘vices,’ to produce positive outcomes. I show that this ‘politics of vice’ emerged as a constitutional principle long before it became a cornerstone of modern economic thought. My work reveals how the eighteenth-century triumph of the politics of vice has shaped both contemporary political institutions and the foundational assumptions of social sciences like Political Science and Political Economy.

My reconstruction first unearths the Renaissance origins of the politics of vice by tracing two intellectual traditions: Machiavellian theories of the passions (from the Florentine secretary to Spinoza) and Jansenist explorations of virtue and self-love. I then focus on late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth century Britain, showing how these arguments were developed both by a Harringtonian constitutional discourse (best exemplified by Trenchard and Gordon’s Cato’s Letters) and in the controversial work of Bernard Mandeville. Crucially, I argue that Mandeville and the Harringtonians shared a number of important constitutional positions. This convergence set the stage for the 1730s and 1740s, when leading British and French thinkers—most notably Hume and Montesquieu—integrated Mandevillean assumptions into their own constitutional theories. Their approaches, however, diverged sharply: Hume focused on interest (defined as selfishness or greed), while Montesquieu proposed the utility of various vices—from interest to honor to ambition—in various contexts. This split proved foundational, driving the politics of vice into multiple directions in the latter half of the century, from the development of Scottish political economy to the American founding.

Revisiting Early Modern Absolutism

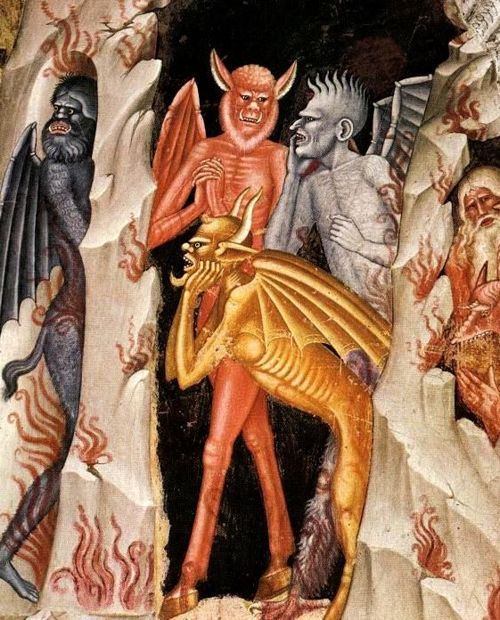

My interest in modern constitutionalism was shaped by my earlier work on its early modern antonym: absolutism. This research resulted in two articles on Jean Bodin (1530-1596) and Robert Filmer (1588-1653). In “Jean Bodin’s Demonic Constitutionalism”—co-authored with my colleague Eero Arum and published in the American Political Science Review—we demonstrate that, in Bodin’s universe, sovereigns are subject to the supernatural enforcement of natural law through demonic intervention. Far from a secularized theological concept, modern sovereignty emerges as deeply enmeshed in a theological framework.

In “Rethinking the Political Thought of Robert Filmer”—published in 2024 in History of Political Thought—I provide a new interpretation of Filmer’s infamous patriarchalism. Refuting scholars who have presented him either as an irrational extremist or as a mouthpiece for conventional commonplaces, I demonstrate that Filmer does not justify sovereignty on the basis of biological generation (as other ‘patriarchalists’ did), but rather through an original combination of divine-right and de factoism. More broadly, I present Filmer as an example of what can be gained through careful conceptual reconstruction of the ideas of authors who hold positions very foreign to our own.

Renaissance Florence: Machiavelli and Guicciardini

I have also worked on various aspects of sixteenth-century Florentine political thought, especially Niccolò Machiavelli and the modern reception of his ideas, including by Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

More recently, I have developed a research project on his friend Francesco Guicciardini (1483-1540). Contemporary scholarship usually portrays Guicciardini as the aristocratic counterpart to Machiavelli’s populist stance. In “Francesco Guicciardini’s Dialogue on the Government of Florence: A New Interpretation”—now forthcoming—I argue instead that Guicciardini’s most sophisticated work of constitutional theory represents a departure from his earlier, more elitist constitutional writings and that, in the early 1520s, he ends up supporting positions that surprisingly resemble Machiavelli’s. After writing this piece, I developed the methodological implications of my interpretation in an article published in Rinascimento in 2024. Focusing on Guicciardini’s Ricordi, I demonstrate that his political thought should be approached in a contextual way, excavating the differences between the specific positions articulated in each work at a specific moment in time. Over the longer term, I aim to develop a series of other studies, including of his letters and unpublished manuscripts, culminating in the first full-scale intellectual biography of Guicciardini.

Future Project: The Politics of Society

It has often been suggested that the concept of ‘society’ emerged in the eighteenth century; the details of its history, however, have never been fully excavated. Questioning the use of the state-society binary itself, a recent wave of historical research has started recovering the variety of ways in which politics was conceptualized before and beyond the state during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. I have myself contributed to this conversation with the article “The Politics of societas and the Early Modern State,” published in 2025 in The Historical Journal. I plan to expand this research into an investigation of the conceptual transformations of ‘society’ in early modern Europe, culminating in Hegel’s canonical distinction of civil society (bürgerliche Gesellschaft) from the state (Staat) in his Philosophy of Right. My research will reconstruct the various types of ‘society’ that did not become part of our modern conceptual apparatus—from the state as a partnership (societas) in the Ciceronian tradition to Mandeville’s society as a body politic managed by government—asking what they can contribute to contemporary reflections on the nature of politics, law, and the economy.